|

|

General J.H. Doolittle

Tokyo Raiders Reunion, 2003

|

|

“Two Ordinary men, One Extraordinary Dream”

Orville Wright once explained that he and his brother, Wilbur, were lucky to have grown up “in an environment where there was always much encouragement to children to pursue intellectual interests, to investigate whatever aroused curiosity.” The sons of a church bishop and his mechanically inclined wife, the Wright boys first became interested in flight as children when their father presented them with a rubber-band-powered helicopter toy of the sort designed by Alphonse Pénaud.

Although neither of them attended college, Wilbur and Orville were intellectual, intuitive, confident, and mechanically gifted. As young men, they operated both a print shop and a bicycle shop in their hometown of Dayton, Ohio. Still, their curiosity and technical skills drove them to pursue other challenges. The death of aviation pioneer Otto Lilienthal in 1896 reignited their boyhood passion for wings.

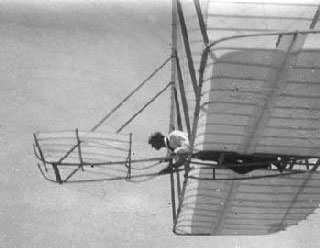

The brothers launched their own aeronautical effort in 1899 after corresponding with both the Smithsonian Institution and the American engineer Octave Chanute. They realized that their first challenge was to find a way to control a machine in the air. They tested their notion of a wing-warping control system on a small kite flown from a hill in Dayton. Between 1900 and 1902, they built three gliders, testing them over the sands of Kill Devil Hill near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina, a location that was ideal because of its high winds and tall dunes, with plenty of sand for soft landings.

Disappointed with the performance of their early gliders, the brothers conducted a series of wind tunnel tests in their bicycle shop during the fall of 1901. On the basis of those tests and their experience with the gliders, they designed and built their first full-scale glider in 1902 and completed 1,000 flights with it, remaining airborne for as long as 26 seconds and covering distances as far as 622.5 feet.

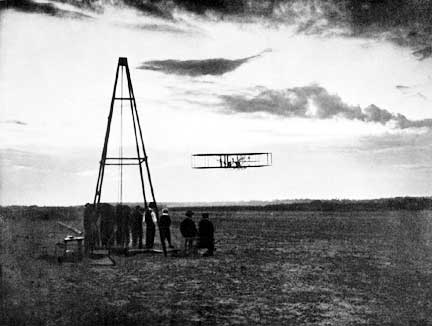

Simms Station, November 16, 1904

Now they were ready to attempt a piloted, powered flight. With assistance from their machinist, Charles Taylor, they designed and built an aircraft and a four-cylinder internal combustion engine that would deliver precisely the amount of power required. They also built the propellers, based on their wind tunnel data, that proved to be the most efficient of the time. Success came on the morning of 17 December 1903. Orville made the first flight at about 10:35 a.m., a bumpy and erratic 12 seconds in the air. A few minutes later, Wilbur flew the plane 175 feet-just a few feet shorter than the wingspan of a Boeing 747. Orville then flew again, a distance of 200 feet. During the final flight of the day, piloted by Wilbur, the Wright Flyer remained airborne for 59 seconds and flew 852 feet.

These four flights marked the first time that a powered, heavier-than-air machine had made a sustained flight under the complete control of a pilot. The Wright brothers were not surprised by their success, for they had meticulously calculated how their machine would perform and were confident that it would fly once they had ironed out all the problems from their previous tests.

Within a few days of these flights, the Wright brothers were the subject of what were, for the most part, wild and inaccurate reports on the front pages of major newspapers from coast to coast. When they did not follow up with public flights in 1904, the press assumed that the Kitty Hawk story had been an exaggeration, of not a hoax.

Wilbur and Orville pressed ahead, moving their experiments closer to their Dayton, Ohio home. There, in 1904, in a meadow called Huffman Prairie, they built the Wright Flyer II, the first airplane to fly a circle in the air. The flyer III followed in 1905, a plane that could stay in the air for more than half an hour, turn, bank, and fly figure eights. The Wrights were determined not to fly in public until they had received the protection of a patent and had signed contracts for the sale of their machine. They ceased flying completely in the fall of 1905 and concentrated on finding buyers for their technology.

In 1908, the Wright brothers finally received due acclaim when Wilbur made public flights in Europe, amazing spectators with his flying skill and the maneuverability of the Wright Model A biplane. That same year, Orville took a Flyer to Fort Myer, Virginia, where he made a demonstration. In 1909, the brothers returned to Fort Myer and sold the world’s first military airplane to the Army.

By 1909, the Wright Company was turning out four planes a month, making it the largest airplane manufacturer in the world. They also formed one of the earliest exhibition teams, flying in various venues where they could publicize and market their planes Orville continue to fly through 13 May 1918, six years after Wilbur’s death from typhoid fever. He sold his interest in their business in 1915 but remained actively engaged in other related pursuits, among them long-running disagreement with the Smithsonian Institution over who had been the first to fly, the Wrights or Samuel Langley. The Smithsonian had originally given the nod to Langley but later acquiesced in favor of the Wright brothers. By the time Orville died in 1948, he had seen many advances in aviation that were a direct result of the work he and his brother had accomplished.

“The Dawn of Military Aviation in America”

1903

- December 17: Orville and Wilbur Wright piloted a heavier-than-air aircraft for the first time at Kill Devil Hill, near Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. Controlling the aircraft for pitch, yaw, and roll, Orville completed the first of four flights, soaring 120 feet in 12 seconds. Wilbur completed the longest flight of the day: 852 feet in 59 seconds. The brothers launched the airplane from a monorail track against a wind blowing slightly more than 20 miles per hour.

1904

- August 3: Capt. Thomas S. Baldwin demonstrated the first successful US dirigible at Oakland, California, flying the airship in a circuit.

- September 20: Wilbur Wright completed the first circular flight at Huffman Prairie, near Dayton, Ohio.

1905

- October 5: The Wright brothers’ Wright Flyer III, the first practical airplane, flew for more than half an hour near Dayton, covering almost 24 miles.

- October 9: The Wright brothers wrote to the US War Department, describing their new flying machine and offering it for sale to the Army. Misunderstanding the offer as a request for funds to conduct invention research, the Board of Ordnance and Fortification turned them down.

1906

- May 22: The US Patent Office issued a patent on the Wright brothers’ three-axial airplane-control system.

1907

- August 1: The Army’s Signal Corps established a new Aeronautical Division under Capt. Charles deForest Chandler to take charge of military ballooning and air machines.

- December 23: Brig. Gen. James Allen, chief signal officer, issued the first specification for a military airplane. It called for an aircraft that could carry two people, fly at a minimum speed of 40 miles per hour, go 125 miles without stopping, be controllable for flight in any direction, and land at its takeoff point without damage.

1908

- January 21: The Signal Corps announced a specification for an Army airship. It called for an aircraft that could fly for two hours, carry two persons, and maintain a minimum speed of 20 miles per hour.

- February 10: The Wright brothers and Capt. Charles S. Wallace of the Signal Corps signed the first Army contract for an airplane.

- February 24: The Army signed a contract with Capt. Thomas S. Baldwin for a government airship at a price of $6,750.

- April 30: Aviation enthusiasts in the 1st Company, Signal Corps, New York National Guard, organized an “aeronautical corps” to learn ballooning-the earliest known involvement of guardsmen in aviation.

- May 14: Charles Furnas became the first airplane passenger when he rode aboard an aircraft flown by Wilbur Wright at Kitty Hawk.

- May 19: Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge flew an airplane called the White Wing, designed by F. W. “Casey” Baldwin, thus becoming the first Army officer to solo in an airplane.

- August 28: After flight tests at Fort Myer, Virginia, the Army accepted Army Dirigible No. 1 from Capt. Thomas S. Baldwin.

- September 3: Orville Wright began flight tests of the Wright Flyer at Fort Myer.

- September 17: Lt. Thomas E. Selfridge of the Army became the first US military member to die in an airplane accident when he crashed with pilot Orville Wright during a flight test at Fort Myer. A propeller split and broke a wire supporting the rudder. The accident delayed Signal Corps acceptance of an airplane for almost a year.

1909

- July 27: Orville Wright, with Lt. Frank P. Lahm as passenger, performed the first official Army flight test at Fort Myer. They flew for over an hour, meeting one of the specifications for a military airplane.

- August 2: The Army accepted its first airplane from the Wright brothers after the aircraft met or surpassed all specifications in flight tests at Fort Myer. The Army paid the Wrights the contract price of $25,000 plus $5,000 for speed in excess of 40 miles per hour.

- August 25: The Army leased land at College Park, Maryland, for the first Signal Corps airfield.

- October 26: At College Park, after instruction from Wilbur Wright, Lt. Frederick E. Humphreys and Lt. Frank P. Lahm became the first Army officers to solo in a Wright airplane.

- November 3: Lt. George C. Sweet became the first Navy officer to fly when he accompanied Lt. Frank P. Lahm of the Army on a flight at College Park. Lt. Sweet was the official observer for the Navy at the trials for the Wright Flyer.

1910

- January 19: Lt. Paul W. Beck of the Army, flying with Louis Paulhan in a French Farman airplane, dropped three two-pound sandbags over a target at an air meet in Los Angeles, testing the feasibility of using aircraft for bombing.

- February 15: The Signal Corps moved flying training to Fort Sam Houston, near San Antonio, Texas, because of the cold, windy, winter weather at College Park.

- March 2: Lt. Benjamin D. Foulois made his first solo flight at Fort Sam Houston. At the time, he was the only pilot assigned to the Aeronautical Division of the Army Signal Corps and, thus, the only one with flying duty.

- March 19: At Montgomery, Alabama, Orville Wright opened the first Wright Flying School on a site that later became Maxwell AFB.

- July 1: Capt. Arthur S. Cowan replaced Capt. deForest Chandler as commander of the Signal Corps’s Aeronautical Division.

- August 4: Elmo N. Pickerill made the first radio-telegraphic communication between the air and ground while flying solo in a Curtiss pusher from Meneola, Long Island to Manhattan Beach and back.

- August 18: At Fort Sam Houston, Oliver G. Simmons, the Army’s first civilian airplane mechanic, and Cpl. Glen Madole added wheels to Signal Corps Airplane No. 1, producing a tricycle landing gear and eliminating the need for a launching rail or catapult.

- August 20: Lt. Jacob Fickel of the Army fired a rifle from a Curtiss biplane toward the ground at Sheepshead Bay Track, near New York, becoming the first US military member to shoot a firearm from an airplane.

- October 11: Over St. Louis, Missouri, in a Wright biplane piloted by Arch Hoxsey, former president Theodore Roosevelt became the first American president to fly.

- November 14: Eugene Ely, a Curtiss exhibition pilot, took off from the deck of the USS Birmingham while it was anchored in Hampton Roads, Virginia, thus becoming the first pilot to fly from the deck of a Navy ship.

Go to the Gonzales Biplane exhibit

Information derived from “Travis Air Force Museum” by Nick Veronico copyright Travis AFB Historical Society/Jimmy Doolittle Air and Space Museum Foundation. This book is available from the Jimmy Doolittle Air and Space Museum GIFT SHOP located in the Travis Air Museum.

|

|