|

Various names have been given to the war, and these have shifted over time, though Vietnam War is the dominant standard in English. It has been called the Second Indochina War, the Vietnam Conflict, the Vietnam War, and, in Vietnamese Chiến tranh Việt Nam, "The Vietnam War" or Kháng chiến chống Mỹ, "Resistance War Against America".

Take-off from Con Son Run Vietnam

The usage of these names may represent a particular viewpoint.

- Second Indochina War: puts the conflict into context with other distinctive but related and contiguous conflicts in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, the prior ending in 1954 and the subsequent beginning in 1979.

- Vietnam Conflict: largely a US term, it acknowledges that the US never declared war on any other party in it. Legally, the US was involved in a "police action," not in a war, and certain wartime legal measures, such as soldiers serving for "the duration," never came into effect.

- Vietnam War: the most commonly-used term in English, it implies that the location was chiefly within the borders of the nation (which is disputed, as many regard the scope as including at least Cambodia); it sidesteps the issue of the lack of a US declaration of war.

- Resistance War Against the Americans to Save the Nation: the term favored by North Vietnam (and after its victory, Vietnam); it is more of a slogan than a name, and its meaning is self-evident. Its usage has been largely abolished in recent years as the communist Vietnamese government seeks better relations with the United States. Official publications now increasingly refer to it generically as "Chiến tranh Việt Nam" (Vietnam War).

Some people oppose the lengthy propagandist term Resistance War Against the Americans to Save the Nation because it does not reflect the civil war nature of the conflict, while others oppose calling it the "Vietnam War" because it reflects a Western viewpoint, not a Vietnamese one. The western view point is though not Vietnamese, but is one portraying the critical cause of war. Given the nature of the government in Vietnam, open discussion even with regard to the name of the conflict is not really possible.

It was a conflict in which the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (DRVN, or North Vietnam) and its allies fought against the Republic of Vietnam (RVN, or South Vietnam) and its allies. North Vietnam's allies included the National Front for the Liberation of South Vietnam, the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China. South Vietnam's main allies included the United States, South Korea and Australia all of who deployed large numbers of troops. US combat troops were involved from 1959 until their official withdrawal in 1973. A large number of civilian casualties resulted from the war, which ended on April 30, 1975 with the capitulation of South Vietnam.

Vietnam Exhibit

The Jimmy Doolittle Air and Space Museum Foundation is honored to have many Vietnam veterans within its membership and as volunteers. Their vast knowledge and personal experiences provided invaluable insight in creating the Vietnam exhibit. The exhibit is entitled “Journey to the Center of Vietnam.”

Major Diana Newlin wrote “Journey to the Center of Vietnam” and conceived and created the Vietnam Exhibit. She interviewed a host of Vietnam veterans, waded through volumes of Vietnam documents, photos and artifacts to create a truly remarkable visual tapestry. This tapestry weaves the Vietnam experience with the dynamic social and political changes that was the hallmark of the 1960s decade. The Foundation is proud to present this exhibit.

Journey to the Center of Vietnam Exhibit

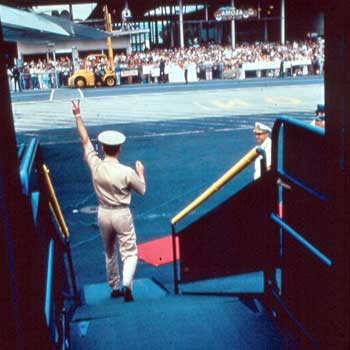

Crowds welcome home Vietnam Prisoners of War at Travis AFB

This exhibit reviews the Vietnam years at Travis from 1960-1975. The exhibit focuses on exploring the Vietnam era, recognizing the struggles of a politically torn America, and the sacrifices of her brave people. To this day many Americans understand little about the history of the Vietnam War and why it is still a painful subject for many of the participants. This exhibit seeks to educate visitors and validate the experiences of the past participants.

The exhibit includes personal accounts of many who lived the Vietnam experience, including some of our very own volunteers. Also recognized are veterans from all branches of the service. Accounts are graphically illustrated by Travis’ own Kathy Kruczek and the display begins with a Free Speech Wall in which veterans candidly speak about their memories and their opinions about their own countrymen who condemned them and Vietnam. This wall is followed by a mural of Vietnam, painted by artist Heide Couch, depicting the scenery of wartime Southeast Asia and Travis AFB. The mural is intertwined with personal stories from aviators, ground troops, medical staff and civilians involved in the Vietnam experience. The object of the exhibit is to hear the story from those who lived it. Despite betrayal, opposition and riots in the U.S., there are accounts of bravery, triumph and above all camaraderie.

Band of Brothers

Carl Bodin, a Travis volunteer described it like this:

“I know it sounds like a cliche now, but the truth is when you fight a war, when you’re involved in battle, you can’t help but become a band of brothers. The enemy feels it too in their ranks. When you put your life in another person’s hands again and again, it forms a bond of trust. This bond is life long. It’s the reason that after so many years, people still come to the Wall searching for those they served with. Then when they find a name, it still releases strong emotions. Even if I met the enemy today, we could still relate. We could relate to this feeling”.

The exhibit displays the faces of war through the years. The uniforms have changed, but the faces appear the same. They are those of young men, determined to defend their country and forever changed by the experience. The same can be said for the women who served. Honored in the exhibit are Babylift participants, military women, civilian volunteers and the Vietnam nurses who shared amazing stories.

“It’s unbelievable how these young nurses faced tragedy day in and day out and through it all had to remain strong to offer compassion to the injured and dying. To be spat on and called names upon their return was not the welcome they deserved,”

From the air support efforts, to the medical evacuations, to the strategic bombing and air war, the Air Force men and women who served in Vietnam never received proper recognition for their often-valiant efforts. This exhibit seeks to render that recognition.

Travis Air Museum News - June 2002

“The Nurses”

Vietnam Nurses War Memorial

By “Big Dot” Dorothy G. Fullick (Maj ret)

USAF Hospital under 12th TAC Fighter Wing Cam Rahn Bay, South Vietnam

One night 27 years ago, I was working the 1900-0700 shift on 6/7 Aug 69. On this particular night, things were busy. Now, I don’t remember any patients’ names from the entire time except the few that are mentioned in this story. And that’s because if you remember you get emotional and lose your objectivity. There was Papasan George, an old Vietnamese gent we’d bring in from Medcap to ease his aches and pains; he was Catholic and had serious joint disease, meaning he really was a cripple. And there was Jimmy, an Army troop who ironically had the physique of Jimmy Brown, the pro football player. Jimmy had meliodosis, an extremely serious disease to have and which must be treated with heavy IV antibiotics. The trouble is that the antibiotics take a toll on the veins and you start running out. About midnight thirty or so, I had just finished restarting Jimmy’s IV, a difficult chore in this case but then again, I have been known to be able to bleed a turnip. All of a sudden, this cacophony starts and it’s getting closer and closer with no let up. My adrenaline goes off the page, getting all the patients underneath the bed. As I made a quick sweep between the two wards, I spot Papasan George still in the bed with hands clasped and praying. I literally picked up Papasan and threw him under the bed, and threatened poor Jimmy that if he blows that IV, I’ll have him before the Cong (enemy). A side note here: we weren’t allowed to have weapons on the wards. They were locked up in a freaking connex! I’ll do my diatribe on the Geneva Conventions as it applies to medics some other time. So knowing we had no weapons, my thoughts are racing and thinking. Hell, the only thing I’ve got here to defend ourselves with is a scalpel and an IV pole. Can ya just see the headlines: Nam Nurse plays Spearchucker!

All the commotion in the world is going on when oddly, the telephone rings. It’s a pilot checking to see if I’m ok. He was on the alert pad and the door to the shack was blown off. Our fearless fighter pilots were out on the line with their flashlights checking for shrapnel on the runway — to protect tires during take-off. And they say, by the way, can I get tomato juice for Bloody Marys in the AM?

In a matter of minutes, here comes the choppers, skids sparking, the crew frantically yelling “Get the patients off! We have a lot more.” Meanwhile, the enemy is still lobbing in mortars and 107 rockets to keep life interesting during this time. The Army’s 6th CC Hospital was about a mile or so from us and sappers ran through the wards with satchel charges and fired AK-47s at the patients as they were trying to crawl out of there! The toll went something like 98 wounded, 2 killed from the Army and on the Air Force side, 2 wounded and 10 aircraft with battle damage. So, this is life. Now, as to them Bloody Marys, yup, the next morning we all gathered in the Goat Bar and were motor-mouthing about the night when in walks an intelligence officer who had gotten smashed the night before and slept through the whole thing! Well, as far as rockets, the year never got much better. Let’s just say it refurbished my understanding of the principles of kinetic energy with a vengeance!

From Oct to Dec 69 we were losing crews at a very steady rate. Our frag mission was resulting in heavy casualties. By Xmas Eve, we had no real reason to celebrate the holiday. All of us were unhappy with 7th Air Force’s strategy of using air crews as human targets.

The 24th of Dec. was my day-off, and I was sitting over in the Goat Hootch Bar with Crash, a fighter pilot. We were drinking beer and discussing this sacrilege. Then it occurred to me to say...To hell with it! Let’s do something for us! “Crash, get the six pack. I’m collecting ration cards and meet me back here.”

So I got in the truck and said, “let’s go to the Class VI store.” Darn...no Irish whiskey so I subbed brandy. Loaded up and went off to the milk plant! That awful “barium” ice cream would have to be the whipped cream! We took a quick stop to the hospital mess to beg the use of a big coffee urn and coffee and we were set! Back at the Goat, I started to brew the coffee and then made Big Dot’s combat Irish coffee.

Well, the word got around and soon everyone started to gather in the bar. We wound up being smashed as we all “serenaded” the place with “Jingle Bells a la Vietnam”.

Now fans if you want to read Big Dot’s rendition of “Jingle Bells a la Vietnam,” you’re going to have to check out the Jimmy Doolittle Air & Space Museum Vietnam Exhibit or go to page 12 at the following Travis Air Museum News.

“Bringing Them Home”

AMBUS Nestles Within the Petal Doors of the Giant C-141 (Starlifter)

In late 1965, the David Grant hospital and its adjoining transient casualty facility had been enlarged to accommodate an increase in patients from the Pacific. In 1968, a $600,000 special construction project added 92 beds to the 2nd Casualty Staging Flight’s transient patient area. Usually patients were held at Travis for more than 48 hours before being transferred to veterans’ hospitals near their hometowns or in Oakland or San Francisco. Even so, by 1970, the number of transient patients had dropped to 2,647 a month. This was still high compared to the figures before 1965, but it represented a respite from the worst of the war years.

The Vietnam War had another, more sobering effect on Travis. This base became the main West Coast Terminus for MAC aeromedical evacuation flights from the Pacific and the principal receiving station for military fatalities that were flown to the United States for burial.

The consequences of the war in Southeast Asia were also clearly apparent at the Travis Mortuary Affairs Office. According to its records, 10,523 military caskets from Southeast Asia passed through Travis in 1968 alone. Army casualties made up 73% of this number. This was because Travis was the Army’s sole receiving station for the war dead on the West Coast until 1970. It was the policy to airlift all military fatalities to the United States as rapidly as possible for the sake of the bereaved families.

Operation Homecoming

Operation Homecoming

Operation Homecoming was the mission to return POWs from Southeast Asia. Between February 12th and March 29th in 1973, North Vietnam released 566 American military and 25 civilian POWs and MIAs, many of whom had spent many years in various communist prison camps. Hanoi’s Gia Lam Airport was the main release point where Miliary Airlift Command’s C-141 Starlifters, took off on 18 “Freedom Flights” returning these heroes to their homeland via Clark Air Base in the Philippines.

One POW remembered the North Vietnamese announcer told the prisoners...

“As I call your name, step forward and go home.”

“Free at last!: That C-141 was the most beautiful bird I’d ever seen! I have chills running all though my body—you will just never know how it feels.”

“Vietnam . . . A Waiting Wife”

Welcome home “Operation Homecoming”

My husband, Ron, flew AC-47s in Vietnam (Class of 68H; Del Rio, Texas). During the time he was in Vietnam, I went home to Milwaukie, Oregon (a suburb of Portland). We had two sons, one 20 months and one 5 days.

During that time, I was a member of the Officer’s Waiting Wives Club, including Warrant Officers. It was an organization which included all of the branches of the military. It was a relatively small group of young women who met monthly to go to dinner, socialize and lift our spirits. I will always remember one gorgeous, exhausted and very brave gal who was the wife of a Navy pilot who had been an MIA for several years. I figured, if she could be upbeat, so could I. I also remember learning how very risky it was to be an Army helicopter crew member. I will always be grateful for the collective emotional strength of that group.

After Vietnam, we came to Travis Air Force Base in October 1969. First Ron flew C-141s and then C-5s. It was a very busy time for Travis. In fact, years later in the Officer’s Wives Club Crosswinds November 1988 magazine, I wrote about it in honor of Veterans and Thanksgiving Day.

“As the years have gone by, I have accumulated many images which have reinforced my gratitude and respect for the American Veteran. None is more vivid than the collage of activities that took place at Travis in 1969. I have always pictured those activities being portrayed in a Neiman-type painting (The Olympics).

I am walking in the passenger terminal with my two little boys, while all around us lines of men, mostly young, are waiting to board the next flight to Vietnam. There are girlfriends, wives, babies, children and parents interspersed among the stacked luggage and lounging GIs. There is a lot of controlled energy...like a Jimmy Hendrix wailing guitar. The place is packed... every race is represented. The Red Cross is busy. In front of the terminal the David Grant medical unit is meeting the Aero-Vac. Some families are not that lucky...I visualize the waiting coffins. I remember the peace demonstrators at the front of the base entrance.

My husband’s latest flight has arrived safely. I see him... hold me...I am grateful; I am proud!”

Hopefully, you too will take time to reflect on the military veteran and those who have kept the “home fires burning” when duty called. Remember them with pride and thanksgiving.

This article was written by Denell Burks, a member of the Jimmy Doolittle Air and Space Museum Foundation’s Board of Directors.

The following photographic collage is available for download as a PDF document.

Click on the image or click here to download.

|